“How many buses can you count in this photo?” by Oran Viriyincy is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Decisions in public transit are often framed as tradeoffs. Should transit service cover a broader area, or should fewer routes run more frequently? What times of day, or days of the week, should see the greatest allocation of service? Rarely will one outcome be superior to another in all ways, for all people. This is the unfortunate reality when limited funding is a hard constraint.

An access measurement comparison, in its most condensed form, doesn’t present an obvious tradeoff. The consequences of any decision are rendered in the form of a single score. Good decisions increase the score, bad decisions decrease it. Of course, this is an oversimplification. The overall access measurement is the composition of many scores. An agency may achieve its greatest overall access by concentrating all of its routes into a section of its service area, but those who must leave that section will be justifiably upset.

The restructured transit network for Seattle that I produced—with uniform frequency meeting or exceeding King County Metro’s definition of frequent service on all routes, all day, every day—increased overall access while using no more in-service hours than the existing network. I nevertheless sought to be cognizant of how this would affect access throughout the city. While some parts of Seattle would see a decrease in access, the losses would be neither severe nor widespread. That still doesn’t cover every way that a restructure could disparately impact riders.

Rather than breaking down the impact geographically, it is also possible to decompose the access measurement over the course of the day. The process remains a matter of counting completed journeys, but instead of grouping them by the origin or destination sector, they are aggregated according to the journey’s starting time. Transit agencies typically vary the amount of service run throughout the day. This is to account for demand and prevent overcrowding. These adjustments also cause significant fluctuation in the quality of access throughout the day. Time-based grouping assesses that variation.

Even after a pandemic that ushered in more flexible working arrangements for some, Seattle still sees its greatest transit use during the traditional rush hours. Transit service ramps up during these peak periods. A quality reduction seems guaranteed under a proposal where the level of service is unchanged throughout the day. And, in fact, the time-based access comparison of Metro’s current service and restructured service does reveal such a reduction. The restructured network introduces a tradeoff between reducing the quality of service at peak, and becoming far less usable outside of that peak. Whether making that tradeoff is prudent requires not just analyzing the restructured network, but examining the role of public transit itself.

Making the Measurement

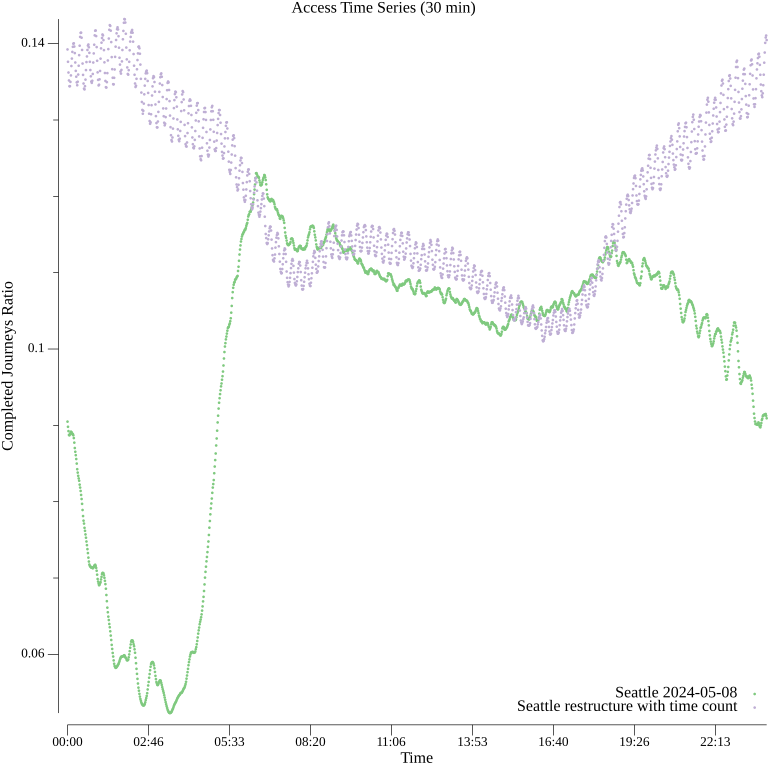

For every minute of the day, I calculated access scores for Seattle, both for the current transit service provided by King County Metro and Sound Transit, and the in-service hour-neutral proposal that I constructed previously. Plotting both of these as a time series allows them to be compared. The results for a 30-minute time budget are below.

The current service, in green, produces very little access in the early morning. Few routes are running, so most of the access is derived from walking. The access score climbs to its apex at the beginning of the morning commute; the steady increase is attributable to routes gradually coming online. From there, access generally drops throughout the day as “tripper” buses go offline, and only all-day service remains. The access increases again for the evening rush hour, as peak service returns. As the evening goes on, and frequencies decrease, access drops.

The restructured service, in purple, has its greatest access overnight. This isn’t intentional favoritism toward those traveling then; it’s a simple matter of buses not getting stuck in traffic when there are fewer vehicles on the road. Since frequency throughout the day is uniform, the access depends entirely on how long it takes for transit vehicles to get from stop to stop. As roads get congested during rush hour, access suffers, even though the frequency of routes remains the same.

The restructured network’s access scores drop below that of the current service during the morning rush hour, though the gap is not wide. At worst, restructured service during the morning peak provides the equivalent of superlative midday access for the current network. Furthermore the present network’s access apex, which it reaches during the morning peak, isn’t impressive compared to the heights that the restructured network reaches. The present network has the benefit of peak service increases—some of which double the frequency of routes—but their impact is muted. The restructured network can’t totally match up with a status quo that invests heavily in peak service, but it doesn’t fall behind by much.

The restructured network’s access dips below that of the present one, again, in the evening peak, but to a lesser degree. There are times in this period where the access scores of the two networks are basically equivalent. Again, the present network gets a considerable infusion of service over its baseline during this period, while the restructured one does not. The peak service investment feels especially wasteful here.

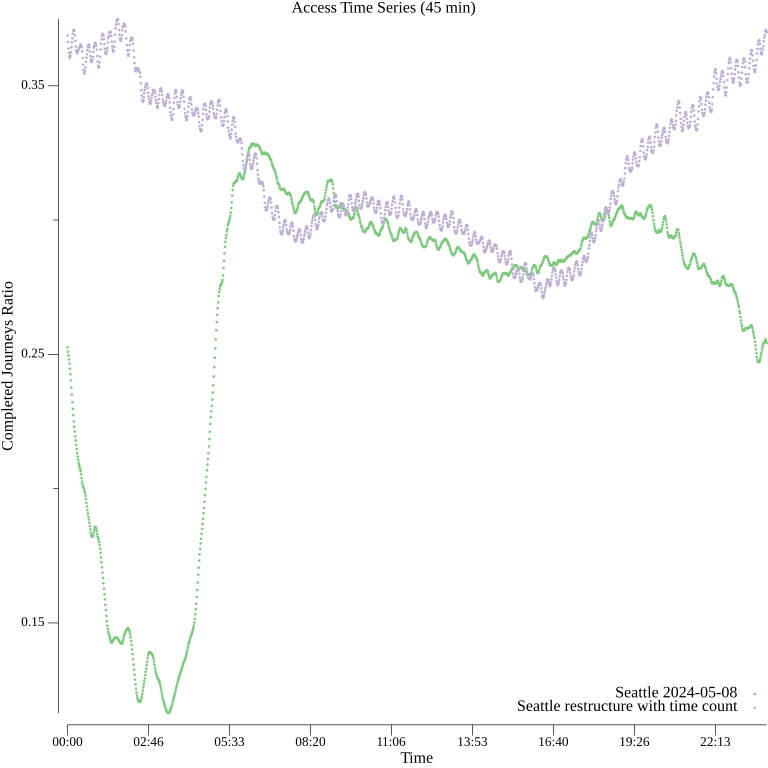

These trends largely hold for a 45-minute time budget.

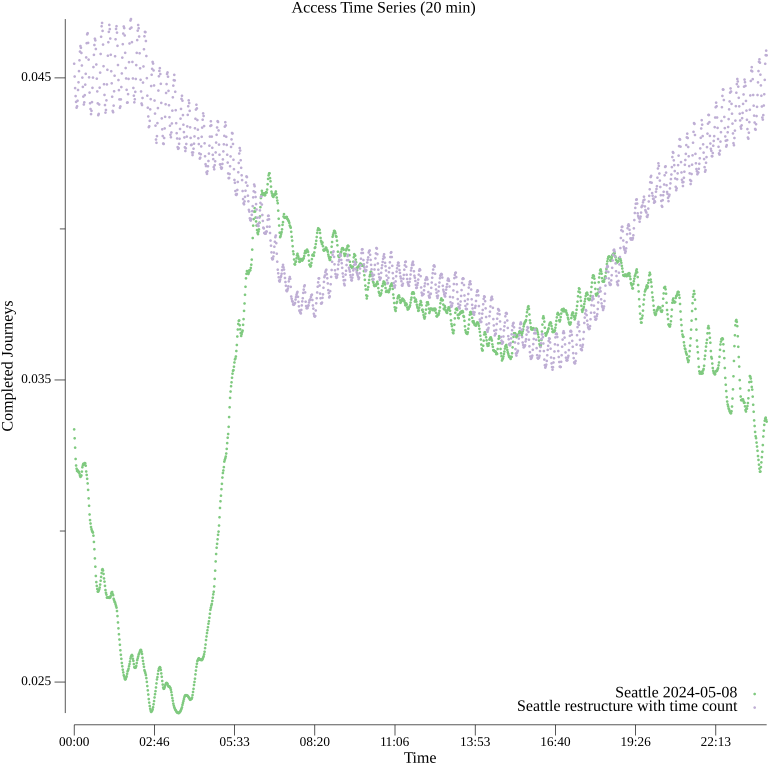

A 20-minute budget yields a similar plot as well.

The restructured service provides not only a higher floor—unsurprising because there’s no period where transit service drops to nearly nothing—but a higher ceiling. That latter property is significant and unexpected, because the restructured service never gets the benefit of stacking a bunch of additional trips atop those that run all day. The restructured network is disadvantaged even beyond that. It runs the same schedule on weekends too, but must not exceed the present service allocation on a weekly basis. In all, it is achieving these results despite a 10% reduction in in-service hours. While adding peak trips does give today’s commuters marginally better access, it has a severe opportunity cost.

Interpreting the Results

Nevertheless, reasonable people can look at these time series access plots and disagree on whether a uniform-frequency restructure is appropriate for Seattle. It’s reasonable to assert that the most people use transit during rush hours, so any change that renders transit less usable then is unacceptable. It’s also reasonable to view ignoring the ability to raise the average, the ceiling, and the floor of the value that a transit network provides to riders as malpractice. Where one stands comes down to a big philosophical question. Is the role of public transit to support or transform the current systems and policies that govern how people get from place to place?

In a supporting role, public transit smoothes the rough edges that emerge from widespread private car ownership. Large numbers of people sometimes need, or want, to get to the same place at the same time. That’s when public transit is useful, even if everyone has a car. White collar office jobs concentrate people living in outlying areas into a downtown. Sporting events bring people from a wide geographic range to a stadium for a few hours. In these cases, taking some cars off the road benefits the majority who remain drivers, by preventing complete gridlock. Outside of that, public transit extends a lifeline to those too impoverished to bear the expense of a car, or unable to operate one. Car use is the preference and aspiration; the present reality is evidence of this. In this view, public transit is a niche product that prevents a car-centric system from collapsing when pushed to extremes. For adherents of the supporting role, the funding that it receives should support this goal first.

If public transit has a transformational mission, then decisions pertaining to it should be in service of displacing an existing, harmful transportation system. Fixed-route public transit would serve as the replacement for the overwhelming majority of personal private vehicle trips, at least within cities. Car ownership would be seen as an affectation, useful to support niche hobbies. Household vehicle ownership would be substantially diminished, removing a significant expense from most budgets. Energy consumption, pollution, and noise would be reduced. Fewer people would die gory, senseless, and preventable deaths at the hands of non-professional drivers. Space once reserved for parking could be reutilized. Road congestion would be diminished, when each person no longer travels in their own multi-ton metal box. This begins a virtuous cycle, since transit gets faster, and thus more frequent, and thus more useful, the less that it is delayed by other vehicles. Transit funding must catalyze this cycle by eliminating scenarios where public transit can’t offer a compelling alternative to a private vehicle trip.

My inclination is toward transformation. Most American adults can’t afford a $1000 emergency expense, while yearly vehicle ownership costs over $12,000 on average. Car crashes are the leading cause of death for those aged between one and 54 in the United States. As normalized as widespread car ownership is, it’s a system that impoverishes and endangers.

Transformation versus support is not a binary, though. I recognize the desire to not disrupt the case where transit currently sees its heaviest use. I would have discontinued support for this restructure if these results indicated that it would render transit unusable during the peak commuting periods. They clearly don’t. Instead, the uniform frequency restructure would result in only a modest reduction in access for commuters. It is sufficiently sensitive to both the role that public transit is currently playing, and the expanded roles that it could play.

It’s time for King County Metro and Sound Transit, and those who advocate for better transit service, to scrutinize the implications that heavily-peaked service allocation have for the current and potential transit riders of Seattle. If the agencies are trying to run superlative service while the most people are using transit, it’s not working. If they’re only trying to avoid overcrowding, then I have yet to find evidence that this needs to be handled by massively stepping up frequencies during peak periods, though I’m continuing to search for data that proves me wrong1. Treating peak service as sacrosanct reinforces a support-only role for public transit, and that’s a terrible outlook for an agency to have.

-

More on this soon! I have data for the Seattle Streetcar, but Sound Transit has quoted a timeline of four to five weeks to provide trip-level vehicle loads. ↩︎